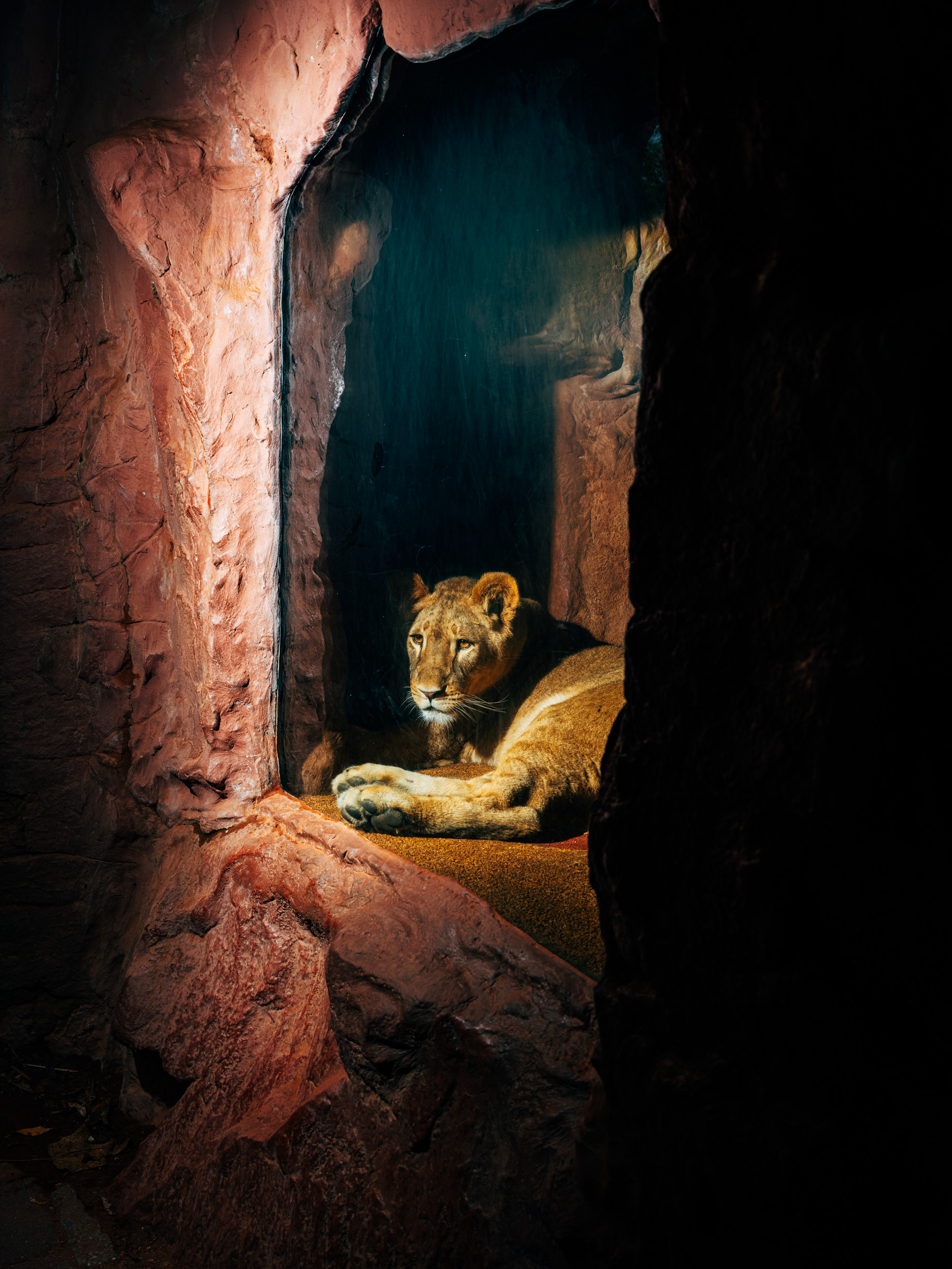

“Life Sentence”

(2022 - ongoing)

Zoos originate in the colonial past of European nation states, where the display of exotic animals and plants functioned as a demonstration of wealth, territorial reach, and power. Visibility was a political instrument: to exhibit life was to claim authority over it. This logic did not stop at non-human beings. Until the mid-twentieth century, so-called “human zoos” existed across Europe, revealing zoological display not as an educational anomaly, but as a coherent extension of colonial domination.

While contemporary zoos often emphasize reform, conservation, and education, the fundamental structure of the institution remains largely unchanged. A central question therefore persists: whether there is any justification for maintaining zoos in their traditional form at all. Most animals kept in zoos today are not critically endangered. At the same time, the substantial financial resources required to operate zoological institutions could potentially protect a far greater number of animals in their natural habitats, where ecological relationships remain intact.

The educational value frequently attributed to zoos is equally contested. Animals confined to artificial environments and insufficient spatial conditions often display atypical or repetitive behaviors that are the direct result of captivity. Polar bears, for example, can travel up to 70 kilometers per day in the wild; in zoos, this movement is reduced to repetitive pacing along enclosure boundaries. Such behaviors do not represent wildlife but rather expose the psychological and physical consequences of spatial restriction.

Ethical contradictions become even more pronounced in the case of great apes. Chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans possess complex cognitive capacities, with intelligence comparable to that of young human children, and have demonstrated the ability to learn structured forms of communication. Under these conditions, the legitimacy of keeping humanity’s closest relatives in permanent captivity becomes deeply questionable.

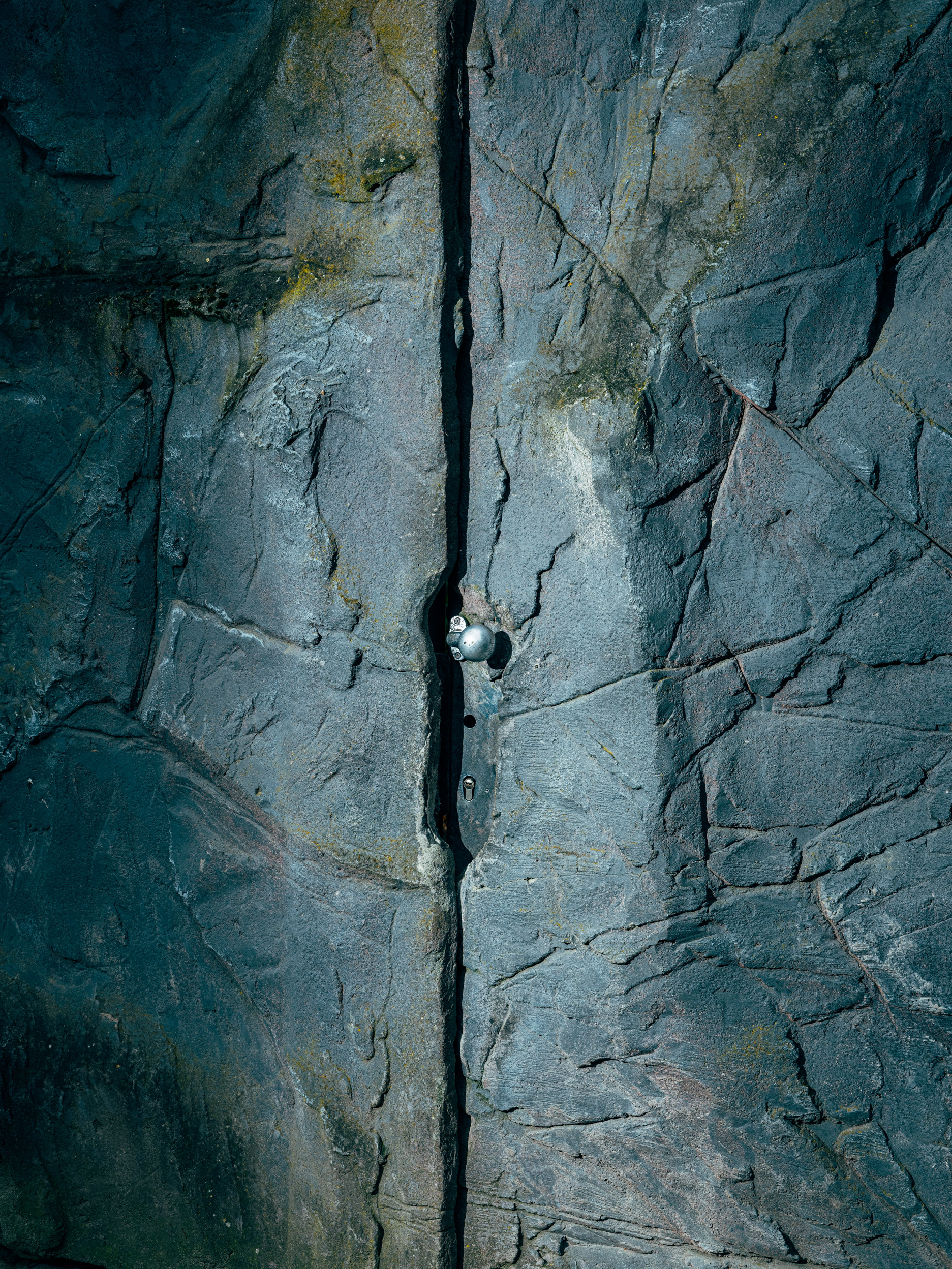

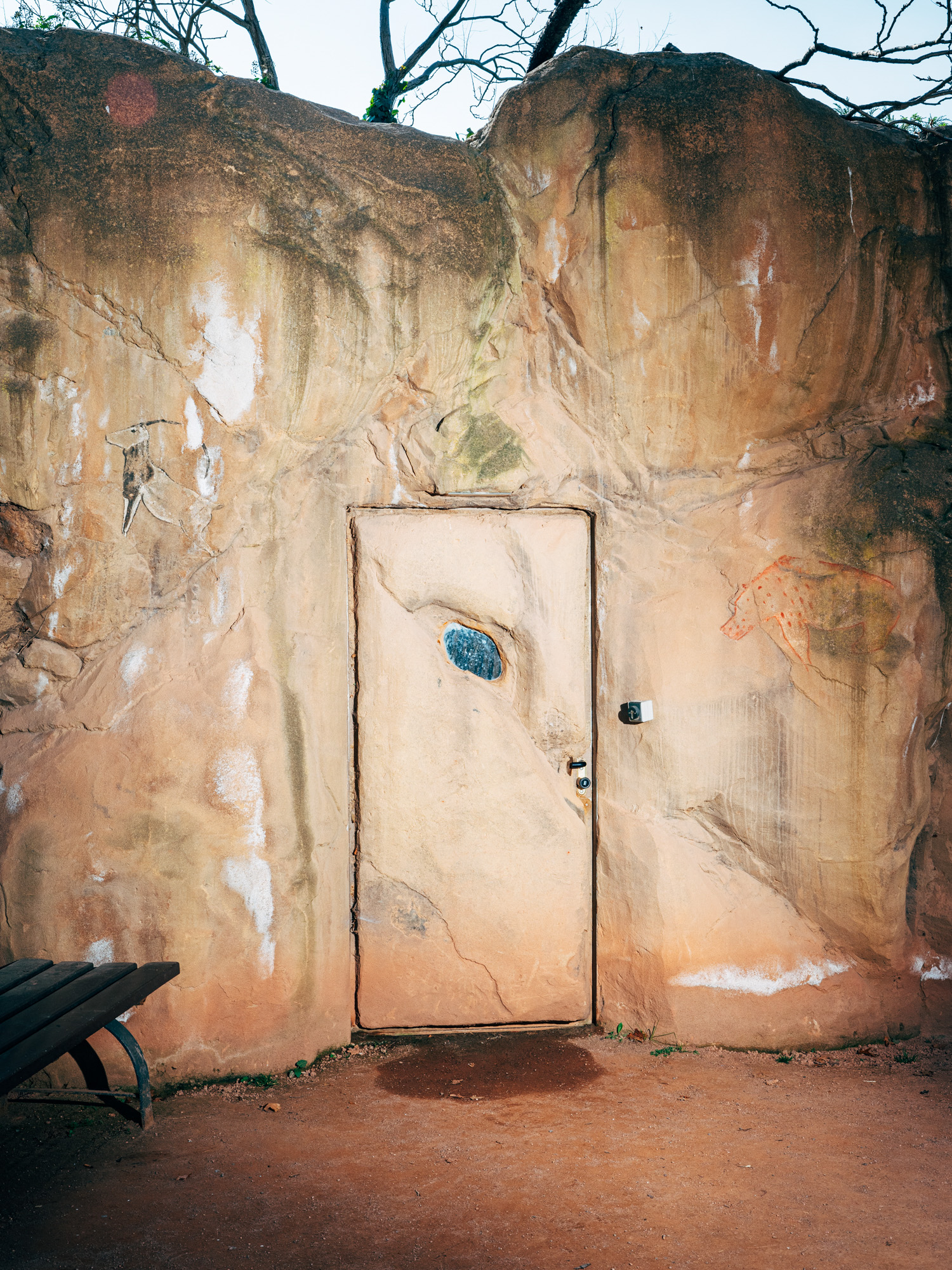

“Life Sentence” understands the zoo as a disciplinary apparatus in which visibility operates as a mechanism of control. To be seen is to be governed. The asymmetry of the gaze—where the human observer remains invisible and unaccountable, while the animal is permanently exposed without agency, constitutes the core violence of the institution. The zoo does not merely display animals; it produces them as objects shaped by enclosure, surveillance, and repetition.

The use of flash is deliberate and confrontational. It functions as a visible escalation of this visual regime, interrupting the fiction of neutral observation. Rather than aestheticizing captivity, the flash foregrounds the violent nature of the gaze itself. The image does not offer consolation or empathy; it exposes the viewer’s participation in a system that equates visibility with domination. It also dismantles the zoo’s carefully staged lighting and reveals the space as it is.

In this sense, the zoo becomes less a site for learning about animals than a space for reflecting on human self-understanding. Visitors encounter not wildlife, but a mirror of the structures through which power, control, and hierarchy are normalized. The photographs in this series were taken in Germany, Switzerland, and Portugal.